Arizona Living Sunday

Francophile learns to make perfect croissant at the master's hand

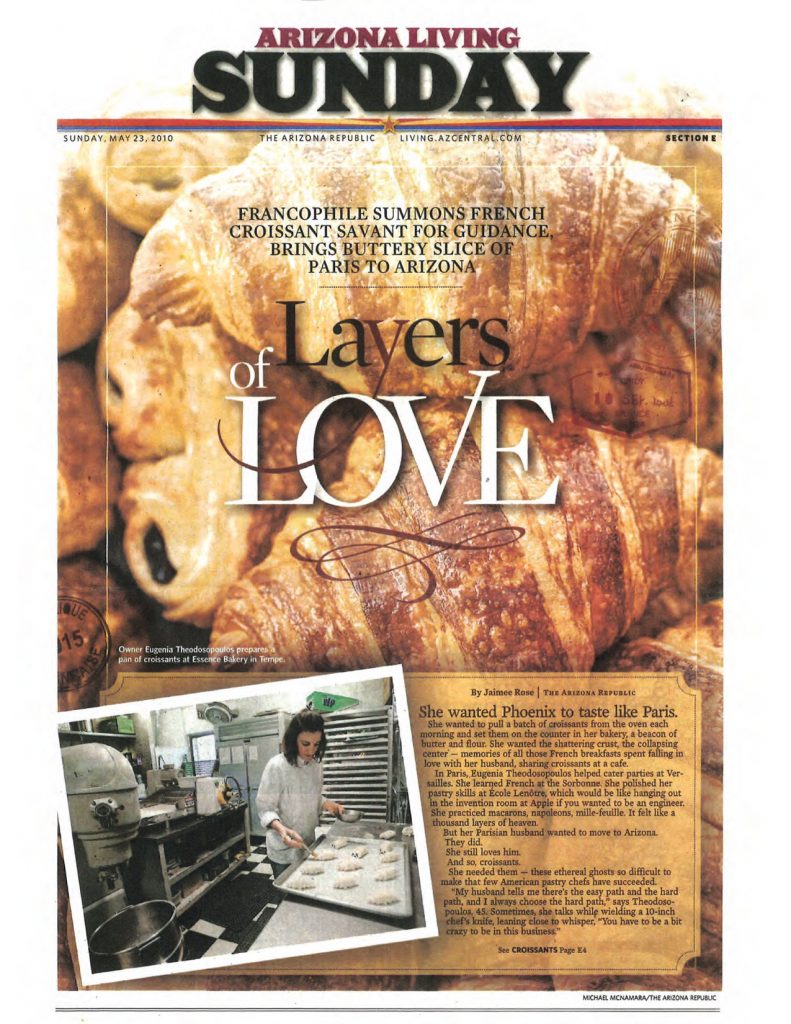

By Jaimee Rose - The Arizona Republic

She wanted Phoenix to taste like Paris.

She wanted to pull a batch of croissants from the oven each morning and set them on the counter in her bakery, a beacon of butter and flour. She wanted the shattering crust, the collapsing center — memories of all those French breakfasts spent falling in love with her husband, sharing croissants at a cafe.

In Paris, Eugenia Theodosopoulos helped cater parties at Vertallles. She learned French at the Sorbonne. She polished her pastry skills at École Lenôtre, which would be like hanging out in the invention room at Apple if you wanted to be an engineer. She practiced macarons, napoleons, mille-feuille. It felt like a thousand layers of heaven.

But her Parisian husband wanted to move to Arizona.

They did.

She still loves him.

And so, croissants.

She needed them — these ethereal ghosts so difficult to make that few American pastry chefs have succeeded.

“My husband tells me there's the easy path and the hard path, and I always choose the hard path." says Theodosopoulos, 45. Sometimes, she talks while wielding a 10-inch chef’s knife, leaning close to whisper, "You have to be a bit crazy to be in this business."

She learned to bake in her family's Ohio diner. At 13, she was in charge of at least 25 daily pies. These days she finishes her 6 a.m. - 3 p.m. jag at her bakery, then goes to the gym to spin like a banshee. After, at home, she cooks dinner. Every night.

"I didn't want to make mediocre croissants," she says. "I wanted to make croissants like you have in Paris."

Croissants require the perfect (French-style) flour, the perfect

(French) butter and e".en a mixing bowl that's cooled just so. If the milk is a half-degree too warm, or if the dough stays in the fridge five minutes too long, or if it's 110 degrees outside in Arizona, the entire enterprise can upend.

To achieve them without the implied presence of the Eiffel Tower and zinc rooftops would be a geographic feat. But in a Tempe strip mall where pizza and Ethiopian cuisine keep company, Greek-American Theodosopoulos is feeding Arizonans 200 perfect pieces of Paris each day: flaky, glorious buttergasms that require three flours, Celsius-Fahrenheit mastery and a ' phone call to an African king. Continental wrangling, indeed.

Crowns

His majesty was offered an apology. The French pastry savant he'd hired to consult on treats for the castle had to cancel and was coming to Essence Bakery in Arizona instead to teach his friend Eugenia to make croissants. (Please understand, the African monarch cannot be identified because one never wants to tick off a king.)

Jean-Louis Clement, 62, is the pastry god that star chefs Joel Robuchon and Alain Ducasse call when they need help with a crust. An instructor at the École Lenôtre, Clément is invited all over the world to share his prowess at a rate of about $2,000 per day. Even the French presidential palace requests him.

He is one of 32 living pastry chefs who have achieved the M.O.F. designation, which stands for Meilleur Ouvrier de France, or "best craftsman." Since pastry is religion in France, this also translates as king of the world. The competition is held every three years, and the chefs prepare...

For the full story, click on image for PDF